by

Malinda Seneviratne

by

Malinda Seneviratne

Physicians know much about the human anatomy. Surgeons, given the nature of their

trade, obviously can be expected to be even more finely acquainted with the internal

organs of the human being. After all, these constitute the bread and butter and much else

besides of their existence. A man who at the age of 91 plus is, according to known

records, the oldest practising surgeon in Asia and probably the second oldest in the

world, accordingly, must have an understanding not just of the organs, but their workings,

break-downs and the possibilities of resurrection, that is proverbially at his fingertips.

There is of course another dimension to understanding the human being and this goes beyond

physiology. Such comprehension can come only through living. Age, then, is also an

indicator of how nuanced one can be about these things, for time is also a teacher.

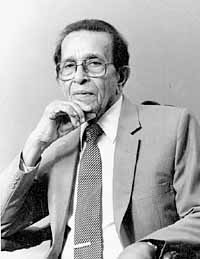

It is therefore no wonder that Dr. Polwattearachchige Romiel Anthonis has over the years received countless tributes, from grateful patients, their friends and families as well as admiring colleagues. Each and everyone of them express both admiration for his skills and a marked respect for his humanity.

I know nothing of anatomy, certainly less than I know about the human condition. My sense is that description of the human anatomy is infinitely more simple than description of the human being, especially a human being endowed with longevity and a penchant for learning. Typically, such people gather encyclopaedic knowledge over the years. Their "profiles" therefore become the work of biographers, not journalists, and this is the thought that I carried with me a couple of Thursdays ago after spending over six hours with Dr. Anthonis, listening to his stories and browsing through various documents. My task, therefore has a one word descriptive: "impossible". I am compelled at the outset to seek Dr. Anthonis’ and the readers’ forgiveness because I can do no better than offer a caricature of the man. The fleshing out, so to speak, will have to be done by someone who is infinitely more competent.

Romiel was born in Bambalapitiya in 1911, the second child of a family of sixteen children. His father, Margris Anthonis Appuhamy (baptised as Michael, although never following the Christian faith), was a carpenter who, after the birth of his third child found employment at the carpentry workshop at Brown’s, later rising to be the supervisor for the handsome salary of fifty cents per day. His mother, Egelthina Perera, was from Kotikawatte, and was the daughter of a well known Ayurvedic physician, popularly known as Juse Vedamahattaya.

Romiel grew up in his father’s ancestral home, then known as "Madangahawatte". "There was plenty of land. Financially my parents were poor, but they were highly respected in the village. My father had had only a little English education, but he was a voracious reader in Sinhala and composed refined poetry."

Dr. Anthonis showed me an exercise book in which he had copied Sinhala verse in elegant handwriting. These included some verses his father had written to his father-in-law, requesting that he be allowed to take his wife home after giving, each successive four lined verse more insistent than the other.

"Father’s three brothers, his widowed sister and our grandmother all lived with us. Father fed them all. There was enough land and plenty of jak fruit which was the perennial food for us. There was enough herbs, vegetables, leafs and we always had a cow at home so there was always milk. Father’s primary concern was to feed us well. He was occasionally helped by his elder brother who had an agency in kerosene oil in Bambalapitiya.

"Everyone loved Mother. She was a very hard working, capable woman and was extremely gentle in her ways. She had an old hand machine and stitched trousers and frocks. Even in the poorest of times, we were well dressed."

When he was six, Romiel was taken to Dharmashalawa (which later became Vajiraramaya), where the Ven. Vajiragnana taught him his first letters, tracing them on the sand. At that time what is now Vajira Road was a narrow red coloured gravel road. There had been thick jungle all around. The road itself was known as "Weli Para". When he was around seven, he was admitted to the Milagiriya Sinhala School.

"My brother, sister and I would walk barefoot to school. I wore a white sarong. Grandmother gave us 5 cents each everyday with which I bought a seeni sambol roll (3 cents), an ice cream (1 cent) and gram or veralu achcharu (1 cent)."

Romiel was born on the same day that the indul kata gahana ceremony was to be held for his elder brother. So they were brought up as twins, going to school, university and Medical College together. The turning point in their education was when their father took them to Rev. Fr. D.J.Nicholas Perera, the Rector of St. Peter’s College Bambalapitiya. He was 10 years old then.

"Fr. Rector said that he couldn’t admit us because it was an English school. My father pleaded. He cried and said there was no other way to educate the children. Fr. Rector looked at me and said that if I tried hard I might be able to succeed. Maybe he felt sorry for us. He gave us three months to pick up our English and said that we would have to leave if we failed to do so. I never played any sports because I went to the library. This is how I developed the reading habit.

"Fr. Rector had instructed the teacher to help us, telling him that if we made a mistake to give a lesson on that mistake. By the 4th standard we were okay in English. And I won the English Prize in the 5th."

Dr. Anthonis showed me a newspaper clipping of the Morning Leader of December 11, 1926. It described the cheers for young P.R. Anthonis as he was awarded prize after prize by Sir Marcus Fernando at the annual prize distribution ceremony. In 1928, Fr. Perera had instructed Romiel’s father, "Your son is getting all the prizes. Get him a pair of long trousers and a rickshaw for the books!"

Whereas his elder brother was groomed to become a doctor, Romiel was encouraged to become a civil servant. The younger son had other ideas. So his father had taken him to Dr.W.P. Rodrigo, who lived at Shrubbery Gardens. Dr. Rodrigo had promised to help in case there was a shortage of money.

At the University College, Romiel had done his "pre-medicals", topping the batch, a feat that is amazing considering that he had never studied Physics and Zoology before. When both the boys entered the Medical College their father had bought them each a Raleigh bicycle.

P.R. Anthonis excelled at Medical College, topping his batch in almost all the subjects. He was awarded the Loos Gold Medal for Pathology, the Matthew Gold Medal for Forensic Medicine, the Rockwood Gold Medal for Surgery and the coveted Government Diploma Medal which had not been awarded for many years. In 1936, he passed out and was appointed as a Medical Officer, as was his brother, Dr. P.J. Anthonis.

It would be impossible to record comprehensively his every appointment and the inevitable stories associated with responsibility and place. So let me in events offer a set of markers that help trace the fascinating journey undertaken by this remarkable man.

He had the good fortune to work as House Officer to Dr. A.M. de Silva. In Dr. Anthonis’ own words, "he was a great disciplinarian and an extremely dextrous technician — spoke very little but a real stickler for time."

He would arrive sharp and 8 a.m. and I would greet him. The ward rounds were a treat. He had the gift of correct diagnosis with little effort. In those days the operation had to be quick as the anaesthesia was chloroform and was toxic to the liver. Sir. A.M. de Silva was a great teacher who taught by example. He never lost him temper. He treated me like his own son. Later, when I was a surgeon, he called me to operate on him. It was not a major operation. I will never forget his contribution to my success." That was how Dr. Anthonis’ remembered his teacher.

In 1939, a new scholarship scheme had been introduced. Dr. Anthonis had been selected to study surgery, along with Noel Bartholemeus. Unfortunately the war broke out and so they had to wait for 6 years. In 1945 he went to the UK to obtain his FRCS and was the first medical man from Ceylon to pass both the Primary and the Final Fellowship in the first sitting. He returned in 1947 and was appointed as Consultant Surgeon to the premier teaching hospital in the island, the present National Hospital of Sri Lanka.

As his reputation as a surgeon grow so did his circle of acquaintances. All people great and small, when it comes down to it, have the same will to live and the same fear of death. The internal organs of the powerful do not work differently. The difference, perhaps, is that the powerful get written about, some because they are exceptional human beings some just because they are powerful. Considering that Dr. Anthonis, operating almost on a daily basis since his retirement in 1971, had handled a total of over 38,000 cases until March 1998 (and still counting, by the way), he would have had the opportunity to dissect the entire cross section of society.

A meticulous man, a bibliophile in fact, he has recorded each of these cases in many registers. When I told him that he had operated on my brother to remove his appendix in 1978, he promptly asked me, "what month?" and later on tried to trace the record. For some reason that particular register was missing, but leafing through those yellowed pages was an experience in itself. Apart from the general descriptions, there were sketches pertaining to the particular operation. There were some days when the man had performed 6 or 7 operations, some of them major ones, taking up several hours.

Among the more "present" personalities in our lives who came under Dr. Anthonis’ were national leaders, diplomats of foreign missions, religious dignitaries, judges of the Supreme Court, professionals of all fields etc. More than half a century is enough time to encounter them all I suppose when you are a surgeon of the calibre of Dr. Anthonis. I am sure each case has its little story, some interesting, some even fascinating, some educational in a medical sense and some just routine. Dr. Anthonis chose to recount at length the case of Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike after he was shot in 1959.

"That Friday morning, I had finished one operation and was about to start on a gall bladder operation. Dr. Mackie Ratwatte called and said ‘My brother has been shot!’. I wanted to know which Ratwatte it was and he said ‘It’s the Prime Minister’. "Where is he?" I asked and Dr. Ratwatte said "outside".

"I asked the Prime Minister, ‘What happened?’. ‘Till that black thing came out, I didn’t know what happened.’ he answered. The ‘black thing’ was the revolver, apparently. I asked him who had shot him and he said ‘a person in the garb of a Buddhist monk’ and went on to describe the incident. ‘I had just met with the American Ambassador. After he went, I worshipped the priest. But doctor, he was a foolish man, please see that he’s not ill-treated’. I advised him not to talk since his pulse was rapid. He would have been bleeding inside.

"He insisted on writing a message to the nation. I told him to cut it short and he smiles, saying ‘we politicians talk a lot’. I told him ‘I need to take a shot of you from the front (meaning an X-Ray)’. He said laughingly, ‘I have already been shot from behind, now its all right shooting in front’.

"I started operating with Dr. K.Yogeswaran, Dr. Mendis and Dr. Peiris. All the other surgeons were standing behind. Dr. M.V.P.Peries told me four times, "stop, heart has stopped’. So I massaged. After the operation I asked him ‘Sir, how do you feel?’ ‘I never felt better in my life’ he replied, adding, ‘please see that my assailant is not treated badly’.

"He slept well. he got up around 4 a.m. His pulse was very good at that time. He wanted to brush his teeth and have some Orange Barley. I informed him that his stomach was in shreds and that he will have to wait. Around 8 a.m. he repeated his wish to brush his teeth. Mrs. Bandaranaike, Sir Oliver and I were there with him. While talking he turned blue, gasped and died. There had been a large blood clot."

Typically I have not spent more than a couple of hours at most interviewing people such as Dr. Anthonis, i.e., those who have excelled in their chosen field. As our conversation ate up the hours, I was worried if I was tiring out this amiable and interesting old man. So I asked him if we should continue the interview later. We had already gone through tea, soft drinks, biscuits and chocolates. He smiled "No, it won’t get done because I am too busy. This is nothing, sometimes I operate for 6-7 hours".

"I tell my students to remove their watches before we start an operation, because until we cut open there is no telling what we might find." The point, I believe, was that certain things cannot be stopped with the explanation "We’ve run out of time", for in his profession, "running out of time" would be a reference to death. Failure.

Turned out that I was the one getting tired, and he is almost two and a half times my age! I confess that in desperation I tried to leapfrog over a couple of decades, for by 8 o’clock (four and a half hours since we started) we were still in the early sixties. He went out of the room for something and when he returned, asked me where he had stopped. I referred to an event somewhere in the early eighties which he had mentioned before he left the room. A half truth, certainly. He smiled and said, "There’s a long way to go before we get to that!"

I couldn’t help smiling myself. For there is certainly a long way left to go.

(Continued next week)