|

Kosgulana range as seen from Sinhagala |

Hinipitigala East and West, viewed from Sinhagala |

The forest is 21 kms long and its maximum width is 7kms. At the narrowest point the width is 3 kms. Sinharaja was declared a forest reserve by way of gazette notification (No. 4046) on May 8, 1875. It was declared a National Heritage Wilderness Site in 1988 and a World Heritage Site in 1989. Sinharaja lies 90m above sea level with its highest point being 1170m above sea level. The annual rainfall lies between 3000-6000 mm, while the average temperature ranges between 23 and 25 degrees Celsius. The total density of flora belonging to each category is around 24,0000 per hectare. |

Text and pic by Jagath Kodituwakku

Spreading over the districts of Ratnapura, Galle and Matara, Sinharaja, our great

tropical rain forest, by all accounts is a vast repository of national wealth. Given its

sheer size, biological diversity and the history therein, Sinharaja naturally eludes

complete description, and is certainly not "capturable" in a single visit.

Indeed even a lifetime of wandering in that enchanting vastness might still not result in

the trees, the ferns, the creatures and the varied textures revealing their numerous

secrets. A single visit, then, must necessarily scratch the surface. What follows then is

a story of what the place yielded over a short period as Ajith Malli and I walked mostly

along known paths with the occasional departure off the beaten track.

Let me begin our story from the point when we are about to climb Sinhagala, located deep within the Sinharaja.

We have now come to the most arduous section of our journey. Several hours had already passed since we started. Our feet ache. For some reason, the haversack seemed to be much heavier on the shoulders than before. The boots, themselves seemingly heavier, has forced us to slow down. Through the dense undergrowth and rocky terrain there suddenly appeared a hill, rising steeply right ahead. Below lay the steep incline we had just climbed. The slightest slip could very well result in serious injury. We are not onto the most difficult and dangerous section of our journey.

An hour has passed since the sun reached its zenith. A full five hours after gulping down a light breakfast, we have now almost come to the end of the journey.

The verdant forest cover stretching in all directions is now visible, just as a lighthouse offers a view of the endless ocean. Such is the density that the trees appear to be clinging onto each other, inextricably bound with one another. The tops of the tallest trees, appear to imitate the ocean waves, as they rock back and forth with the wind. At times they are as still as a monk, deep in meditation. The scenery all around was breathtaking. Far away a Serpent Eagle was gliding ever so slowly, presumably focused on its prey. The mysterious silence of the jungle was occasionally broken by the incessant chirping of crickets.

All around us lie the great tropical rain forest, Sinharaja, subject of much controversy, in view of moves to bring it under the hammer of untrammelled plunder by way of the Tropical Forest Conservation Act of the USA. Sinharaja is steeped in history. In fact it is claimed that this forest had its origin in the ancient forests that covered the lost continent of Godwanaland. As that giant land mass broke up, the portion that remained in this island came to be known as Sinharaja.

Covering a total area of 118425 acres, according to folk lore, this forest was first known as the "Sinhalaye Mukalana" (Forest of the Sinhale whose boundaries were unseen), and later came to be known as Sinhalaye Raja Vanaya (The Royal Forest of the Sinhale) and finally shortened to Sinharaja.

Sinhagala is the most prominent of all the nine peaks that are found in Sinharaja. There are interesting folk stories about the name Sinhagala. Some have it that a long long time ago, there lived a lion in a cave at the foot of the hill. The ancients believe that this lion ruled a vast extent of land and a giant had thrown massive rocks and eventually killed the beast. This "cave" is supposed to have been called Sinha Lena (Cave of the lion) and the place where the rocks thrown by the giant lay, "Yoda Gal Goda". This is the story that was related by Ajith Malli, a volunteer tracker of the Sinharaja Conservation Office, Kudawe.

Martin Aiya, better known as Professor Martin due to his vast knowledge of Sinharaja, who is from an ancient village bordering the forest, had a different story to tell. According to him, there is no cave anywhere near Sinhagala capable of housing a lion. As for the rocks, he claimed they were unearthed over the years by gem miners.

There are many points of entry into Sinharaja. One could come through Kalawana; by way of Veddagala, from the Eastern side; through Rakwana Morning Side Estate; from the Southwest, the Beverley Estate in Deniyaya; from Northeast through Daffodil Estate, Rakwana; and from the Southeast, through Kosmulla along the Hiniduma-Neluwa Road.

Once we reached the peak our weariness seemed to have evaporated. In fact a sense of invigoration quickly enveloped us. It was a privilege to stand upon the summit, gazing upon all that lay beneath, transfixed in wonderment. The natural beauty surrounding us was spiritually uplifting and it infused into me certain sensations that will allow me to relive that calm contentment again and again as long as I have life and memory.

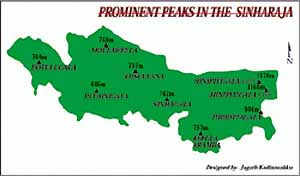

I inquired from Ajith Malli about the two proud hills that rose from the South. "Those are named Hinipitigala West and Hinipitigala East. There are a total of 9 such peaks within Sinharaja. These are the tallest among them. They are 1170m and 1168m in height, respectively. What you can see far away on your left, is Kosgunala (797m). Next is Mulawella (760m). Sinhagala is 742m in height." He said that we had walked about 14 kms to come here, perhaps allowing me to ascertain the relative distances.

It was well past lunch time, and Ajith Malli and I munched on cream crackers, washing it all down with the little water that remained in our bottles. We spent a long time enjoying the splendid scenery around us and started on our way down again. Making our way along the stream that lay at the foot of Sinhagala was difficult because the stones were slippery. We crossed the stream and came to a thick glade of Nelu. Walking through it increased our weariness several fold.

As anyone who has been to Sinharaja would agree, there is no escape from the hordes of leaches that infest the undergrowth. The only thing to do was to allow these creatures to have their fill of blood. A lot of people who venture into Sinharaja show an unusual degree of revulsion and fear at these creatures. The previous day, I had the opportunity to witness a bevy of young Russian girls screaming and running in all directions. Their faces were red. They carried on their white skins blotches of purple, the sure sign of a leach attack, so to speak. Their faces and their voices betrayed utmost terror.

I found Ajith Malli stopping every now and again, scratching his entire body. Clearly embarrassed, he offered that there were more leaches around these days on account of the rains. "We were lucky that the sun was out today. It has been raining hard every evening for the past several days".

The Heen Dola was moving at its usual leisurely pace. We stopped to rest awhile, listening quietly to the soothing sound of the stream. In this stream can be found the Bulath Hapaya (Black Ruby Barb — Puntius nigrofaciatus), Gal Pandiya (Stone Sucker — Garra ceylonensi), and the more rare Pathirana Salaya (Barred Danio — Danio pathirana). Apparently there are 20 species of fish in Sinharaja, among which seven are endemic to the area.

There are 12 species of mammals to be found in Sinharaja, of which eight are endemic to Sri Lanka. Kola Wandura (Purple faced leaf monkey — Presbytis senax vetulus), Gona (Sambhur— Cervus unicolour), diviya (Leopard — Panthera pardus kotiya), Olu Muwa (Barking deer— Muntiacus muntijak), Wild boar (Pus scrofa) are found here.

There are both native and migratory birds here. A total of 20 species have been documented here among which 18 are endemic to Sri Lanka. Among these are theKehibella (Sri Lanka Blue Magpie — Cissa oruata), Vatharathu malkoha (Sri Lanka Red Faced Malkoha— Phaenicophaeus pyrrhocaephalus), Anduru Nil Mesimara (Sri Lanka Dusky Blue Flycatcher— Musciapa sordida).

There are 19 species of amphibians, of which 10 are endemic, 65 species of butterflies of which 21 are endemic have been documented. Among the butterflies found in Sinharaja are, Common Bird wing (Troidus helena), Blue Mormon (Paoilio Polymnestor), Blue oakleaf (Kallima philarchas). There are 72 species of reptiles, of which 21 are endemic.

Needless to say, the rich fauna includes colourful flowers, ferns and vines, blending harmoniously with the great trees. Among the more common flowers found in Sinharaja is the Hambu or the Bim Orchid (Arundina graminifolia) . There are two varieties of the carnivorous Bandura, the green one (Nepanthus distillatoria ) which is the more common and the less common red one, Rathu Bandura. The latter is said to have curative properties, especially in the treatment of whooping cough.

In a nearby branch was a wonderfully woven cobweb, reigning over which was a giant spider. The female of the species is said to be larger than the male. My guide, diligently took the trouble to educate me about these things. I listened to him as attentively as my need to capture these images in photographs permitted me.

"This spider is called the Mookalan Makuluwa. It is also called the Kele Makuluwa. The scientific term is Nephia maculata. In English, "Wood Spider". The large one with the black and yellow spots is the female. The male is more reddish in colour.

"This is an Aridda tree (Compnosperma zeylanica). This is endemic to Sri Lanka. It grows up to reach the canopy. Nearby is the tree Ginihota (Tree fern — Cyathia walkeri). This is one of the largest ferns endemic to the country. Long ago, our ancestors are said to have used this to light torches."

Now we are near the Research Centre of Sinharaja. This is used for research purposes by the Botany Department of Peradeniya University. Around three hundred and fifty meters from here is a majestic Navanda tree. Its trunk must have been about 21 feet in circumference. It was about 145 feet in height. The light was too poor for a photograph. We had already walked more than 25 kilometers. We were dead tired, naturally. Darkness was pursuing us. It was gradually encroaching on the surroundings. We still had a couple of kilometers to go. And still, the joys of the journey and the wonders we had encountered and indeed were encountering each moment served to lighten our hearts and take away the pain in our bodies.

We were now close to Martin Aiya’s place, "Disithuru", haven for itinerant travellers such as we. As the darkness descended the mysteriousness of the forest grew and enveloped us. The lamp light from Martin Aiy.a’s house twinkled like fireflies in the distance. I quietly soaked in the deep silence.

It was already very cold. Still, it was a night I knew I would cherish simply because the following day I would be returning to the dust-filled, noisy city, teeming with people and full of the cacophony of koththu roti boutiques. Tomorrow and on tomorrows to follow, I would have to really on dreams, dreams of another time like this, another journey of discovery and amazement.

My sincere thanks to Sinharaja Conservation Project Forester Mr. Ananda Brahkmane, R. F. O. Mr. K. G. Gunasekare and Tracker Mr. Ajith Priyantha